A director, an editor, a producer and Mr. Glass were camped in an editing studio near Canal Street in Lower Manhattan at 2 a.m. earlier this month, making the last push to finish the 40-minute pilot of "This American Life" for Showtime. "This is everything that is really slow about production, times 500," Mr. Glass moaned, summing up the four-month process.

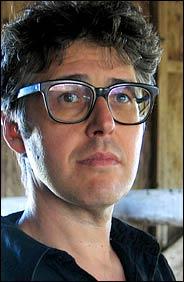

Mr. Glass, 46, has broken a lot of the rules of radio with "This American Life." Each week its three segments, contributed by a cast of regulars and a variety of guest writers, thinkers and soulful eccentrics, are loosely organized around a theme like "Fiasco," "Reuniting" or "Mind Games." But the themes are almost incidental; it is the show's literary quality and Mr. Glass's offbeat production values that give them their intense power and appeal. Mr. Glass uses strategically placed breaks and music, along with droll asides and occasional audible giggles, to spin tales filled with irony, suspense, paradox, drama and humor out of the stuff of everyday life. The show has explored with equal vigor the worst production of "Peter Pan" ever staged and the despair of the second intifada. And it has given major career boosts to writers like David Sedaris, Sarah Vowell and David Rakoff.

Mr. Glass, 46, has broken a lot of the rules of radio with "This American Life." Each week its three segments, contributed by a cast of regulars and a variety of guest writers, thinkers and soulful eccentrics, are loosely organized around a theme like "Fiasco," "Reuniting" or "Mind Games." But the themes are almost incidental; it is the show's literary quality and Mr. Glass's offbeat production values that give them their intense power and appeal. Mr. Glass uses strategically placed breaks and music, along with droll asides and occasional audible giggles, to spin tales filled with irony, suspense, paradox, drama and humor out of the stuff of everyday life. The show has explored with equal vigor the worst production of "Peter Pan" ever staged and the despair of the second intifada. And it has given major career boosts to writers like David Sedaris, Sarah Vowell and David Rakoff."This American Life" now has 1.7 million listeners on more than 500 stations, representing one of the biggest audiences on public radio and turning Mr. Glass into a kind of matinee idol for a certain bookish-but-hip sliver of the population. It has won a Peabody Award and a duPont-Columbia Award for broadcast journalism. David Mamet credited Mr. Glass with "reinventing" radio. But Bill McKibben, writing in The Nation in 1997, unwittingly pointed up Mr. Glass's current predicament when he bestowed this compliment: "None of the pieces I've heard on 'This American Life' would work well on TV."

Indeed, few shows since the era of Jack Benny and Burns and Allen have survived the transition. A number of public radio shows have tried and failed many times. "Television is the opposite of radio," said John Hockenberry, who spent 12 years as a reporter and host at N.P.R., followed by nine years in television at NBC. "TV speaks to a crowd, and radio speaks to a single pair of ears."

Nonetheless, the offers from television began arriving after the show's first year in 1995. For a long time, Mr. Glass demurred. But Showtime was persistent.

"We knew that if he could translate it visually, it could be something special," said Robert Greenblatt, the entertainment president of Showtime Networks. And Mr. Glass and his staff of six producers (three in Chicago with him, and three in a Brooklyn Heights office) were eager to attract new audiences - and money. [Read more -- you'll have to subscribe to read it all, but it's free]

2 comments:

I'm terribly in love with Ira Glass.

Hey, you have a great blog here! I'm definitely going to bookmark you!

I have a 50 bulletproof cent game video site/blog. It pretty much covers ##KEYWORD## related stuff.

Come and check it out if you get time :-)

Post a Comment